FERNANDO GÁLVEZ

PICTORIAL JOURNEY TO THE NATURAL ESSENCE

Something very important in the ensemble of Saemisch’s work is that over his 65 years of prolific production as a painter and draftsman, 99 per cent of his work was made on paper with various techniques. To make hundreds of small-sized art pieces in pastel, crayon, watercolor, gouache, inks or just charcoal or pencil speaks about a stance on art that differs from that of most painters. Saemisch used to go out to look for art in the streets of cities and villages, the mountainous nature of the Swiss Alps, the German Black Forest or the tropics of Guerrero in Mexico, but also on the deck of a boat or along beaches and oceans. Art was embedded in life itself and in death moments; existence’s pulse in its intense and ephemeral character needed to be captured with quick, fluid lines. To achieve this, the painter couldn’t be confided for weeks working on a painting.

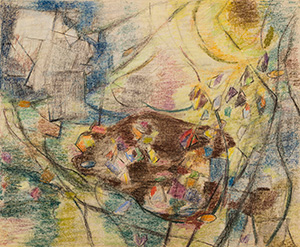

When I first encountered this artist’s work, I used to think that his life circumstances, the same ones that made him constantly change his residence, also compelled him to work on small sheets of paper. But after studying his work for more than 30 years, I concluded that this was a deliberate, conscious, and fully decisive position for approaching with visual poetry the very moment when the encounters with landscapes, people, and other events occurred. Even if he was in his studio working with pastels on a subject he had seen or experienced on previous days, what he wanted was to capture the sensorial and intense flow of thought in the very moment he was thinking, remembering, and feeling. It was a desperate attempt to convey all the feelings that emerged when one came across, for example, a tree, an autumn tree lit up by sunlight, a tree as an organic flash in the middle of urban geometry, a tree that breaks the grid of the buildings and the straight line of the street, bursting and cracking in its golden leaves, its shape fitting and replicating itself in each leaf that composes it. The succession of ideas and feelings that unleashed at first impact rushes onto the paper , the pictorial or drawing decision leaves no room for hesitation. As he said -and now I understand it more than ever- “Each day, painting is like jumping into the abyss.”

Although in the formal adventure that each of Saemisch’s series implies, the avant-garde (Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Futurism) seems to be anthologized, actually, all of them are used as tools subservient to the poetic impulse of capturing the instant’s vitality, the essence of the scene depicted, its life force, the existential magnificence nested in each brief moment. The watercolors choose an image and poetically evolve; in each sheet, a step forward is taken to the metamorphosis of the object, person or landscape chosen. Poetic tropes emerge. The tree in the light becomes a stained glass window that integrates the urban architecture into a weave of rhombuses; the original fiery tree has transformed into a formal chromatic composition in which the tree and the cityscape merge to encapsulate the atmosphere of the first view in an eminently poetic solution that resolves the contradiction. Tree and city no longer contrast; instead, they merge into a unified image.

Even though inks used as gouache or watercolor have produced extraordinary art throughout European history, it is actually in China and Asian art where they have had a very widespread development. In 1920 at the Kassel State Art Academy, Saemisch befriended a Chinese classmate who showed him the art of his country, and, I dare to say, he learned more from him than from that Academy. The creative stance I described earlier, as well as the frequent use of watercolor and paper, seems to empathize with the classic ideas of the Asian artistic disciplines. However, when it comes to aesthetic solutions, Saemisch drew upon contemporary European avant-garde artistic movements. Germany during the Weimar Republic was the epicenter of a rich intellectual, artistic, and scientific life. Art galleries in German cities, as well as magazines and publishers, featured the best of the German and European avant-garde. Saemisch attended exhibitions with so much excitement and empathy that he quickly sought to escape the Academy’s restrictive premises. Eventually, he enrolled in the early years of the Bauhaus, the European avant-garde school par excellence.

In his “Windows” and “Cities” series, one can discern the profound impact of his teacher Lyonel Feininger, who created The Cathedral of Socialism, a woodcut used as a cover for the Bauhaus foundational manifesto. Also, Saemisch’s work in series and small formats seems linked to Paul Klee’s lessons. Though Klee was not yet a permanent Bauhaus teacher, he was already giving talks, lectures, and lessons while negotiating his contract with principal Gropius.

I insist, Saemisch goes to every exhibition he can and treasures throughout his life catalogues from artists such as Munch, who left a mark on many of his early works, or Alexej von Jawlensky, Russian expressionist artist who made an extensive series about feminine faces, evolving from expressionism to geometrical simplification and almost until abstraction. These books, kept by Saemisch’s widow and son at the Association that promotes knowledge of his work in Mexico, are historical editions recording exhibitions or of the first editions of these artists’ works. Saemisch kept them even when possessing such materials meant risking his life during the Nazi dictatorship, as Hitler had classified all avant-garde art as “Degenerate art”. Thus, Saemisch himself was a degenerate artist; his aesthetic stance, influences and Bauhaus education, were considered the product of idiocy, madness, depravity and decadence according to the ideology behind Hitler’s massive exhibition on this subject. That exhibition had a dual purpose: to display, what he deemed, according to him, the moral degeneration of this art and the art from Africa, Asia and America, and also to organize painting and, above all, public burnings of books. Additionally, he sought to sell art collections to his equally “degenerate” friends, in order to rid the country of what he considered spiritual contamination and to finance his military project.

Saemisch’s works unequivocally opposed the absurd, racist, and reactionary totalitarian ideas of the Führer: his pieces clearly show this, as we can see not only in his devastating portraits of leaders and members of the Nazi party, but also in his critique of their use of the death penalty with his series about the electrocuted.

His work as a whole shows the plethora of names that had an impact on him and shaped his aesthetic thought and artistic proposal. This is seen in his “art dialogues” with paintings by the likes of Picasso, Kandinsky, Klee, Matisse, Cézanne, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and more. For example, in the “tree” series, which I’ve already mentioned, he draws upon Mondrian and his namesake Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, leader of the expressionist group “The Bridge”. Saemisch looks at Kirchner`s exaltation of the city through eyes of the pedestrians on the street, exaggerating and making the most of the angles and architectural elements to transmit the city energy and using fashionable suits, shoes and hats as elements to sharpen the urban vitality. But Saemisch transforms this lesson in another thing, he isn’t interested anymore in the intensity of urban life, what he wants is emphasize natural elements that survive in the middle of the urban design: “the true life survives on that tree”, seems to say, and far from vitalize the artificial and skillfully made city, he uses it to contrast the organic and full of life, poetry and spirit always in nature. What is natural is the essence of everything because we all are part of nature. In his “Flags” series seems to be influences of the chromatic and formal uses from the Dance by Matisse, but what really interests Saemisch is to paint the dance of the wind and even if he uses a manmade flag to express it, what inspires him is to make visible the nature of the air, the dancing gusts, just like also in other series he makes the airflow visible through movement of the trees.

For Saemisch, human beings are supporting actors in the theater of life. There are moments when he doesn’t address them at all, and many times when he does, he praises them by merging them with the elements from the natural universe, like in the “Fishing” series, the fishermen dissolve into the sea, blend with the light and the atmosphere. The act of fishing interweaves the sea, its waves and fish, the sky, and the water connected by celestial lights and the horizon. The shore, in turn, merges with the salted waters, the swaying of the tide, and the rhythm of the fishing motion.Everything becomes a colorful poetic language that drives the human spirit to dissolve into the elements of nature: liquid and oceanic rhythm, air and luminous atmosphere, the beach, earth transformed into sand caressed by foam, sun’s fire turned into glowing crystals, into particles of color that alternate with the iridescent shimmer of the fish.

When Saemisch finally departs from life, he does it through cosmic fragments, far removed from the fear of death, the screams, and the terror of World Wars; all his work walks among his red expressionist mountains, which seemed crystallize at the peaks into blues and whites because of the snow. Also distant are the vast stone farmyards that traced signs at the top of mountain range, the shadowed and aromatic density of the Black Forest from his childhood, and of the family country house. He advances through mountains revisited time and time again with his paintbrushes much like Cézanne, though if the French master sought to make Mont Sainte-Victoire a pictorial object, Saemisch strove to transform his painting into a space for the organic manifestation of the natural landscape.

From the heights, the lake in “Valle de Bravo” reflects a mirrored cloudscape, beams of light falling and materializing, making the sun’s rays palpable in temperatures translated into translucent watercolor tones. In Mexico, during his final years, his connection with nature feels so immediate that he is once again able to return to human subjects and intertwine them with the elements of the natural world—just as he had wished when painting European peasants and sailors in his youth. But now it’s effortless. His hands have acquired wisdom, his gaze penetrates deeper, and the landscapes settle within his mind and his being. His creative impulse no longer falters at the edge of the paper’s abyss, now the colors flow freely; the lines, the figures, the compositions align into a universal, transcendental order, and his poetry archives everything he ever sought to express. He is already cosmic matter, rather than leaping, he now swims within the vastness of nature itself.

FERNANDO GÁLVEZ DE AGUINAGA